Cambridge

Sir Adrian Cadbury (King’s 1949) has spent a lifetime promoting ethical standards in the boardroom, says Peter Richards. And it’s largely thanks to him that corporate governance is transforming the way we do business. Why greed isn’t good?

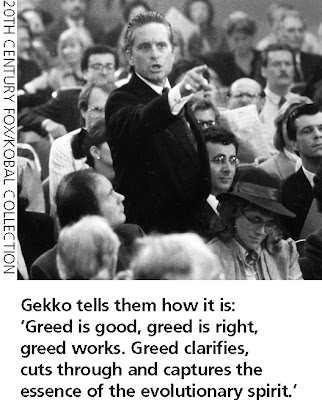

Watching Oliver Stone’s Wall Street in a cinema on the Upper East Side is one of my abiding memories of the eighties: seduced from the first cheesy moments by Sinatra singing ‘Fly me to the moon’ as the camera pans over a fiery dawn in lower Manhattan, then pinned to my seat by the sheer gusto of the performances. As a film it has its faults. But no one ever forgets Michael Douglas’s Oscar-winning turn as the cutthroat financier Gordon Gekko, or his ‘Greed is good’ speech to a shareholders’ meeting that is the turning point of the movie.

Gekko is suitably reptilian: all candy-striped shirts, power braces and slicked-back hair – the very archetype of unbridled capitalism, concerned only with the next deal and contemptuous of the interests of any ‘little people’ – employees or shareholders – who get in the way. He’s the snarling villain who steals the show; not some hapless victim like Sherman McCoy in Tom Wolfe’s blistering

The irony, of course, is that Wall Street became a call to arms that fired up a whole new generation of tycoons. Fuelled by what Ronald Reagan used to call ‘the magic of the marketplace’, the greedy eighties bounced back in the nineties as the dot.com boom, and they’re still alive and well today (albeit a little wobblier since August). Nine of the top ten buy-outs of all time have been announced in the last year.

Business can still be gladiatorial, but top executives have become sticklers for the rules – not least because white-collar fraud can now get you a life sentence. Bernie

With the collapse of the Soviet empire, capitalism became the only game in town. So the key public interest issue now is how we regulate: not just the stock exchange roller coaster John Maynard Keynes famously called ‘casino capitalism’ but corporations themselves. At least that’s the message of Adrian Cadbury’s friend Bob Monks, the lifelong Republican who pioneered shareholder activism in the

Still mulling this over, I crest a humpback-bridge over a canal and come abruptly on Cadbury’s house, crunching to a halt beside the duck pond. It’s a handsome, half-timbered

In person Cadbury is tall, spare, self-deprecating, immensely courteous and endlessly interested in people: not their foibles and absurdities but their abilities and interests. Born into the Cadbury chocolate dynasty and still an Eton schoolboy during the Second World War, at

The river became a lifelong love affair. He stroked King’s first boat in the Lents and Mays, and then in the 1952 Boat Race rowed in the only Blue Boat ever to contain two Kingsmen (his compatriot was George Marshall).

It was one of the outstanding contests in Boat Race history, rowed in a snowstorm but remembered above all for the closest finish since the dead heat of 1877. At Barnes,

Cadbury’s consolation that summer was to row for

When Cadbury joined the family firm in 1952, he brought with him not just the famous pink socks and hippo tie of the Leander Club but attitudes to corporate life drawn from his Quaker background and from rowing: a set of values completely at variance with Gordon Gekko’s rampant egotism. Remembering that last hectic summer training on the

It was Cadbury who over a generation steered the company into the modern world. Until

The board itself was in the front line. With help from the management consultants McKinsey, says Cadbury, ‘we gradually moved from being a board of management, which met at 9am every Monday morning, to being a directing board’.

In 1969, determined to achieve critical mass in the world market, the company merged with Schweppes, a long established drinks business that looked an ideal fit, both ideologically and in market terms. Cadbury had to sell the deal to the family shareholders, but found inspiration in his Boat Race defeat.

‘There was a certain amount of inertia at Cadbury. We weren’t doing badly, so there was no real motivation to go through the trauma of a merger, but that was too similar to the ‘52 Boat Race attitude. It reminded me of that sensation of feeling comfortable, but dangerously so. I felt the time was right, just as I did when stroking.’ The merger finally went through and proved an outstanding success. Over the next thirty five years turnover increased from £260 million to £6.7 billion.

Over time, what did become clear was that the food strand of the merged business didn’t fit with the rest. In 1986, the company’s food, coffee and tea brands such as Smash, Chivers Hartley, Kenco, Typhoo and Marvel were therefore sold in a management buyout to a team led by Cadbury- Schweppes then planning director Paul Judge (Trinity 1968). Judge borrowed £90,000 to invest in the new company, Premier Brands Ltd, which he then transformed into such a roaring success that he was left £45m the richer when it was sold on three years later.

In 1990 he gave a generous £8m to

What Adrian Cadbury didn’t forsee when he stepped down as chairman of Cadbury-Schweppes at sixty was that he was embarking on a new career that would quickly shred any notions of retirement. Convinced that better, more effective boards were the key to good business decisions, he put his thoughts together in a little book called The Company Chairman (1990). Concise, free of jargon and full of good sense, it had an immediate impact.

Then, in the wake of the Polly Peck and Coloroll scandals, where accounts showing companies to be in good shape had been published just weeks before their total collapse, Cadbury was invited by the London Stock Exchange and big City accounting firms to chair a committee on financial corporate governance that would come up with a code of good practice.

Within weeks, new upheavals stretched their terms of reference.

‘It was not a big report. We made nineteen recommendations, and most of them are one sentence. But the essence was disclosure: you must be open about the way you’re running your business. Particularly in a publicly quoted company, the equations can become difficult. But your job as directors is to balance your duties towards your investors, your employees, your consumers and society as a whole.’

Issued in December 1992, the ‘Cadbury Report’ proved a watershed that thanks to its chairman’s tireless advocacy continues even now to make waves around the world. Later reports and fifteen years of academic research have only served to uphold the fundamental Cadbury principles of openness and transparency.

Some publicly traded companies still do not separate the jobs of chairman and chief executive or have on their boards three or more outside directors, as Cadbury recommended, but increasingly they are seen as mavericks about whom investors can draw their own conclusions.

In 1992, Cadbury recalls, even after the BCCI and Maxwell scandals, there were plenty of naysayers who said, ‘Who are these people? This is interference with the way businesses are run’. The Confederation of British Industry didn’t like the recommendations, even though both it and The Institute of Directors had been represented on the committee.

‘They gave me the chance to have my say at the CBI conference, so they could oppose such intervention. But I really believed in what we’d done, so I was prepared to speak anywhere, to any audience, and say, “We believe that these things are in your interest – and if you don’t meet the expectations society has of you as directors, you are going to have regulation imposed on you.” In the event, I got almost total support from the CBI membership.

‘Our code of practice had no legal force. All we asked companies to do in their annual reports was to comply or explain why they weren’t doing so. There were all kinds of people who didn’t wish to comply: until very recently [the supermarket group] Morrisons didn’t. Fine. They explained that to their shareholders, and their shareholders initially supported them. It was only when things began to get a bit rocky that they had to make changes.’

One unexpected consequence of the report has been a huge amount of travel, says Cadbury. ‘I’ve been to 24 different countries, some of them several times, to talk about corporate governance and reporting. And it’s that concept of “comply or explain” that has had such impact internationally. It’s been taken up by the World Bank, right across Europe, and taken root almost everywhere except the

This transatlantic split reflects a genuine ideological divide, says Cadbury. Gordon Gekko wouldn’t agree that companies have any ethical responsibilities to the society in which they operate. They exist solely to make money, which is why the mantra ‘greed is good’ is hardwired into so many brains. Ethics exist only to be left at the office door with your coat.

As the free-market economist Milton Friedman once put it: ‘Few trends could so thoroughly undermine the very foundations of our free society as the acceptance by corporate officials of a social responsibility other than to make as much money for their stockholders as possible.’ For Friedman, a corporation’s sole ethical imperative is to stay legal.

So what does Cadbury think companies are for? ‘The fundamental role of a company is to provide the goods and services people want, and to do so efficiently, ethically and profitably,’ he says. ‘Companies are chartered by society. They have a legal existence; they have benefits; and in return there is an implied contract with society. Companies need to deliver the benefits society expects from them. Why should they have favoured status otherwise?’

On that definition, he says, corporate governance is the job of ‘holding the balance between economic and social goals. The aim is to align as nearly as possible the interests of individuals, corporations and society. The incentive for corporations is to achieve their corporate aims and to attract investment. The incentive for states is to strengthen their economies and discourage fraud and mismanagement.’

The contrast is stark. In continental Europe and

‘For business,’ says Cadbury, ‘the dilemma we are faced with in questioning the American way, of course, is that they’re very successful. Their companies work very well. In

‘Many benefits flow from the changes we have made in

Recently Cadbury pulled together the fruits of his earlier and later careers in a further, equally crisply written, book, Corporate Governance and Chairmanship. A Personal View

In other words, as one early Cadbury statement of aims so admirably puts it, ‘nothing is too good for the public.’

No comments:

Post a Comment